The church where James Stone grew up refused to perform his funeral but members attended to cause the family additional grief

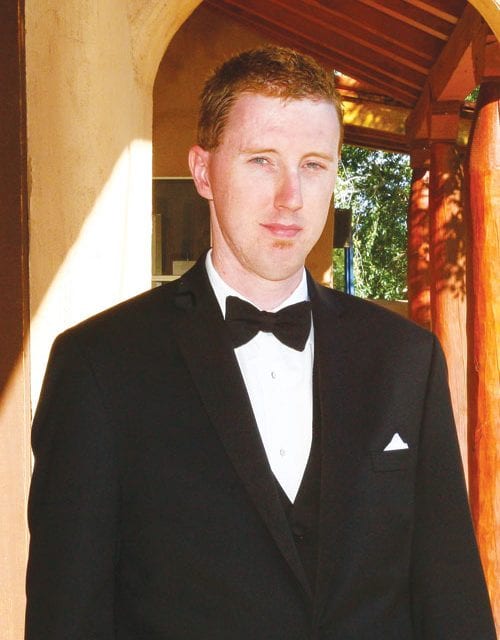

WWJD | James Stone wanted to be burried next to his father in a Mountain Home, Ark. cemetery. But, pastors in Clarkridge, where his family is from, refused to perform his funeral. (Courtesy Jay Hoskins)

DAVID TAFFET | Senior Staff Writer

When Vicki and Jerry Oels and other members of Clarkridge Church of Christ attended the funeral of a gay man in Mountain Home, Ark., they may have gone a step beyond even Westboro Baptist Church.

The members of Westboro stand across the street with their silly signs, but never really approach any of the mourners. The Oels — and others from Clarkridge Church of Christ — actually attended the funeral and stood graveside within feet of the mourners. The couple then handed an envelope to the chaplain who performed the service, to the dead man’s mother and to the dead man’s husband. In each envelope was a “sympathy” card, along with 18 pages of hate-filled rhetoric telling the dead man’s friends and loved ones they’re going to hell.

Jeremy Liebbe, the chaplain who performed the funeral service for 32-year-old James Stone, said he knew something was up when he saw the smirk on Jerry Oels’ face throughout the service. Liebbe said he opened the envelope they gave him already expecting the hateful literature that was inside.

Liebbe said his response to the Oels was, “If you think I’m going to hell for this I’ll see you there, because you’ll be there before me.”

Liebbe, who originally reported the story to Dallas Voice, said initially that the churches contacted were in Mountain Home. The churches were actually in Clarkridge, an unincorporated area about 10 miles away.

Jay Hoskins, Stones’ widow, said most of the people who attended the funeral refused to step into the tent and take a seat. Only seven of the dozen chairs were occupied, even though about 30 people attended.

“To have these idiots show up and do this was the most awful and cruel thing that they could have been done,” Hoskins said.

Hoskins described his husband as having been bullied all his life, beginning when Stone was in fourth grade and continuing until he dropped out of high school at age 16.

Stone got his GED and went to college.

Stone got his GED and went to college.Hoskins said Stone was so distraught when his father died he tried to commit suicide, but he maintained a close relationship with his mother.

Hoskins and Stone met online in 2004. When Stone introduced Hoskins to his mother, it was the first time he ever introduced her to anyone he was dating. That was how he confirmed to her he was gay.

Hoskins said when he first saw Stone, it was love at first sight and was the first time he ever felt loved and accepted.

Stone moved to Paris, Texas to live with Hoskins. The couple was living in Conroe, Texas along with Stone’s mother, Joan, when Stone died.

Last August, on their 10th anniversary as a couple, Hoskins and Stone were legally married in New Mexico.

Hoskins said Stone suffered from Sjogren’s Syndrome, a genetic autoimmune disorder. He was taking a new prescription that Hoskins believes may have caused a severe psychotic episode. On Jan. 19, he and Joan Stone were out of the house and when they came home, they found Stone dead. He had hung himself.

Hoskins, who is trained as a paramedic, was unable to revive his husband.

Montgomery County did its part to make the death even more difficult for Stone’s mother and husband.

Since Texas doesn’t recognize same-sex marriages, Joan Stone gave Hoskins power-of-attorney out of respect for her son’s wishes and because of her own health problems. The county refused to accept it and insisted her signature appear on documents as next of kin. Hoskins is listed as “person providing information.”

The death certificate issued by the county lists Stone as single.

Next, Hoskins contacted the church where Stone grew up about doing the funeral. Stone wanted to be buried next to his father in the family’s cemetery plot in Mountain Home.

From Texas, Hoskins called the only churches he knew in Clarkridge — Clarkridge Church of Christ and Clarkridge Baptist Church.

According to the Baxter Bulletin, the local newspaper in Baxter County where Clarkridge and Mountain Home are located, the pastors of both denied being contacted.

Hoskins said he was told by both churches that they would not perform a funeral for someone who is gay.

The Rev. Jim McDonald is a rector at St. Andrew’s Episcopal Church in Mountain Home, and he said he or someone at his church certainly would have assisted.

“I don’t know what church or churches were contacted, but I assure you the family would have received a different response from St Andrew’s Episcopal Church,” McDonald wrote in a comment on a blog post about the situation at DallasVoice.com.

The Rev. Eric Folkerth of Northaven United Methodist Church in Dallas said he couldn’t imagine a UMC church not offering a grieving family some solace and assistance by performing the service or, at the very least, referring the caller to someone in the area who would. He said it’s what any decent human would do and certainly anyone who called himself a pastor should do.

The Rev. Eric Folkerth of Northaven United Methodist Church in Dallas said he couldn’t imagine a UMC church not offering a grieving family some solace and assistance by performing the service or, at the very least, referring the caller to someone in the area who would. He said it’s what any decent human would do and certainly anyone who called himself a pastor should do.“It should not be hard to go to a funeral and support a grieving family, no matter who died,” Folkerth said.

Since Hoskins wasn’t from the area, he said he didn’t know who else to call. So he contacted Liebbe, a former police officer. The two men had worked together in Hunt County, and Liebbe was the first person Hoskins introduced to Stone after they became a couple.

Liebbe, who said he does “occasional chaplain work,” added that he has taken basic course work in interfaith studies and services, which he used as a police officer.

“In police work, I learned to give comfort and steer someone toward counseling,” he said of his chaplain’s training.

So Liebbe traveled to Mountain Home, near the Missouri border, to perform his friend’s funeral.

After the service, Liebbe said, Hoskins and Joan Stone had hoped to have fellowship at the community firehouse. Stone’s father built the firehouse, according to Liebbe, and it’s custom for them to open the building after funerals for people from the town who have requested it.

Arrangements were made for the fellowship time at the firehouse. But a couple of hours before the funeral, it was canceled. Stone’s aunt, Ruth Strain, had booked the firehouse and Hoskins found out this week it was Strain who canceled the dinner. Commenters on Dallas Voice claim it was other church members who canceled the reception. Whether or not those other church members were involved, their comments seemed to take pride in hurting the grieving family.

A representative from the firehouse called Hoskins this week to apologize for the misunderstanding and confirmed it was Strain who canceled. He said Hoskins and Joan Stone were welcome anytime and they’d be happy to cook them a dinner.

Hoskins said he’s afraid of putting up a grave marker in the Mountain Home cemetery because he worries it will be desecrated or stolen.

“But James wanted to be back home and buried next to his dad,” Hoskins said.

After the funeral, Joan returned to Conroe with her son-in-law and Hoskins plans to continue taking care of her rather than sending her back to Arkansas to live with her other sons.

Over the loss of his husband, he’s inconsolable.

“I don’t know how I’m going to go on without him,” Hoskins said. “He grew up in a backwards town and couldn’t be himself. He hated how cruel people could be.”

This article appeared in the Dallas Voice print edition February 6, 2015.