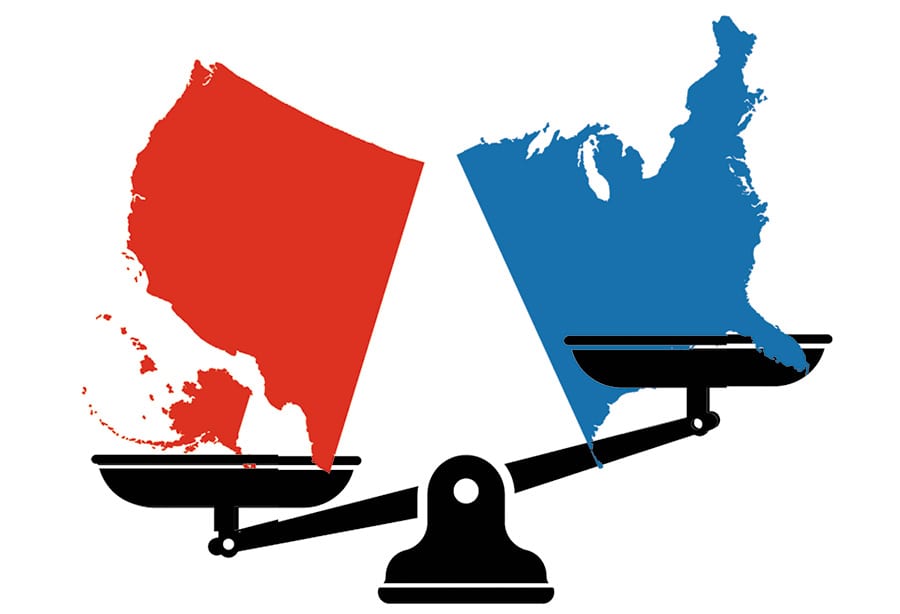

In this age of such deep partisan divisions, suspicion and hate, a fair trial may not even be possible

Recently, I received that familiar letter in the mail from Dallas County informing me that I was cordially invited to jury duty. I am probably different from most people; my first reaction wasn’t “Aww crap, how can I get out of this?” I find the process if not fun at least interesting and, often, educational.

Recently, I received that familiar letter in the mail from Dallas County informing me that I was cordially invited to jury duty. I am probably different from most people; my first reaction wasn’t “Aww crap, how can I get out of this?” I find the process if not fun at least interesting and, often, educational.

So I notified work that I would be out on this particular Monday, and I headed for the Frank Crowley Courts Building with a positive attitude, an open mind and a good book — just in case.

I was directed to the Central Jury Room, which is a huge waiting area. Periodically, messages and instructions were announced by Jury Services. Then a judge came down and swore us in as a group, and after a while, we were assigned to our courtrooms by group.

I won’t give the court number I was assigned to, but about 70 of us were asked to report. At 11 a.m., the judge sent us to lunch without us ever seeing the inside of the courtroom, and since the food court was being renovated lunch option consisted of food trucks.

At noon, we returned upstairs where we were given questionnaires and assigned juror numbers. When we were called into the courtroom, we were seated by juror number, and that’s when the prosecutor and the defense attorney began questioning us. It’s a process called “voir dire,” where each side can question prospective jurors to weed out those who may be biased for or against the accused, for one reason or another.

It was during this process that I realized again, most vividly, just how divided we are as a country.

Ordinarily, whether a person has a prior conviction can’t be mentioned in the guilt/innocence phase of a trial. But this case was an exception. The defendant was charged with being a felon in possession of a firearm, so we knew right off the bat the prosecution would show the accused was convicted of a prior felony, though we had no clue as to what kind of crime he had been convicted of.

People are often mistaken when they say you are entitled to a trial before a jury of your peers. You aren’t. You have the right to a jury trial before an impartial jury.

Yeah, good luck finding that. It’s a nice thought though.

The bias exhibited by this panel was widespread and segmented. Some raised doubts they could judge the defendant fairly if the defendant didn’t testify — even when they were reminded of the Fifth Amendment’s guarantee that a defendant has the right not to testify and not have that refusal used against them.

Here, in essence is what happened:

Court: “Here’s the law, the Constitution our country was founded on. Can you respect it in this case?”

Jurors: “Nope.”

Court: “According to the rule of law, the prosecution may provide as few as a single witness, and if that witness is convincing beyond a reasonable doubt, the state is entitled to a conviction. Can you apply that law?”

Jurors: “Nope, we need more.”

Someone suggested that police can’t be trusted because they have shot unarmed African-American people. While true, that doesn’t really have any bearing on this case.

The accused was using a Spanish language interpreter. The panel was asked whether anyone had thoughts on that. Many did: “If they are in this country, they should speak English.”

No one ever mentioned how long the accused had been in this country, and the defendant’s immigration status was not discussed. Yet the bias was clear.

The question was raised as to whether a person with a previous felony conviction could get a fair trial. Several members of the panel said, essentially, “No, if they have a felony they probably did it.” I heard more than one prospective panelist musing as to what the felony might have been.

This defendant never stood a chance of getting a fair trial; biases — in both directions — were so numerous, they ended up “busting the panel.” That is, everyone was sent home. They will have to start over from the beginning if they decide to proceed with trial.

It was discouraging to me to hear so many people — who I’m sure would very much want to be tried by an impartial jury if they were ever in the defendant’s place — refuse to hear only the facts in the case, apply the law as written and set aside prejudice or preconceived notions, difficult though that may be, and render a verdict that is fair and just.

That is at the very foundation of polite society.

I wonder if that system is irretrievably broken. I sure hope not.

Look, people who violate the law, who hurt or kill others, who steal or harm children or animals — if they are convicted of those crimes — ought to suffer the consequences, no doubt about it. But we can’t let our society become a well-dressed lynch mob.

Every single defendant is entitled to the presumption of innocence, and the burden of proof lies solely on the state. That’s the law.

We are entitled to our day in court. Let’s all work to ensure that day, when it comes, is before a jury who is fair, engaged and impartial. We are entitled to nothing less.

Leslie McMurray, a transgender woman, is a former radio DJ who lives and works in Dallas. Read more of her blogs at lesliemichelle44.wordpress.com.

I loved reading your article! You presented a very good case. Innocent until proven guilty. That is the law of the land. Yet, we now see a Judge who has been accused on allegations of rape. In other words, the way it has been viewed by some is that this judge is guilty until he can prove his innocence. Knowing individuals from communist countries has helped me appreciate our laws. IF we as a nation decide to allege anyone guilty before finding them innocent, then we have become the communist nation and would be no different.

Thank you again for sharing your juror experience. I found this most enlightening and refreshing! Well done!