They Both Die at the End

author Adam Silvera. (Photo courtesy of K.W. Strauss)

Books for, and about, people of all ages like you

Titanic Summer by Russell J. Sanders (Harmony Ink Press 2018)

Titanic Summer by Russell J. Sanders (Harmony Ink Press 2018)

$16.99; 250 pp.

“Your mom and I have some news.”

Those are words that no 12-year-old boy wants to hear, but Jake Hardy heard them and everything in between: his parents were getting a divorce.

That was four years ago, and Jake survived, more-or-less. He wasn’t happy when his dad moved from Houston to Philly. He wasn’t happy that his mom got all churchy, either, but he knew that his parents both loved him. He wasn’t sure, though, how they’d feel if they knew that he was gay.

Jake had, in fact, just come to that realization himself in the past year or so but he wasn’t sure where to go with it. His school was conservative Christian and homosexuality was forbidden in the school code. Jake couldn’t risk being thrown off the basketball team, so he hid his physical desires. He now had the whole summer to think about everything, and make some decisions.

Fortunately, he’d do that while hanging out with his dad in Philadelphia. Unfortunately, his dad had other plans: he was a history buff, and was seriously obsessed with the Titanic. He’d watched the movie hundreds of times and, to Jake’s dismay, had scheduled a ten-day father-son trip to Halifax, Nova Scotia.

That’s where some of the Titanic’s dead were buried. That’s also where gay-boy Jake learned that his dad was gay, too.

Which was just great, because Dad could’ve been less-secretive and that would’ve helped Jake deal… but no. Instead, Jake got secrets and omissions from both his parents, which made him angry and his bestie offered no sympathy. He found a new friend, but even that was awful. Was pretending not to be gay the easiest way to live?

Though it tends to be somewhat overly-long and overwrought, Titanic Summer is overall better than average. Part of that may be because Sanders puts authentic teen language into the mouth of his main character. Sanders’ Jake speaks in the style and manner you’d expect from an attitudinal 16-year-old boy who’s trying to please everyone; that he fails, and sometimes becomes unlikeable, only enhances his realism.

That authenticity affects the story itself, but in one distracting way: the plot is enough to keep a reader’s attention, but it’s also too long and contains inconsequential details, as if every second of the titular summer needs recording. A few editorial snips would have been a lifesaver.

Even so, that’s minor compared to the waves of enjoyment you’ll get from this story, whether you’re 13-to-17-years-old, or an adult who’s well past those years. Readers craving a coming-of-age novel will find Titanic Summer to be a boatload of goodness.

They Both Die at the End by Adam Silvera (HarperTeen 2017) $17.99;

They Both Die at the End by Adam Silvera (HarperTeen 2017) $17.99;

373 pp.

The phone call came shortly after midnight. Mateo wasn’t expecting it… but then, who expects a call from the Death-Cast, anyhow? He thought about not answering the phone, but there was no getting out of it: his time was up. He was going to die, and the worst part was that he was going to die without talking to his dad first.

Mateo’s father was in a coma and if he ever woke up, someone else would have to tell him that Mateo was gone. And that was that: he’d spent all his time with his dad and his gamer stuff and he didn’t exactly have any true friends he could count on. No, Mateo Torrez was going to die, just 18 years old, alone, in a tiny apartment. But first, he downloaded the Last Friend app.

The phone call came just after 1 a.m. Rufus was beating the heck out of his ex-girlfriend’s new boyfriend then, and everybody figured Death-Cast was calling Peck. No, it was Rufus’ phone that was ringing. Rufus was going to die.

He’d been through this before: four months prior, his parents and his sister had all gotten the call on the same night. He’d been in an orphanage since then because he was only seventeen, almost an adult, a milestone he’d never make.

He couldn’t let his friends watch him die and so, just after Peck called the cops to report the assault, Rufus bolted. Spend his final hours in jail? No way, so he downloaded the Last Friend app. Maybe someone could show him where the “old Rufus” was.

The match came a little after 3 a.m. Rufus had a bike. Mateo had a few dollars. Neither had much time.

And telling you any more than that would ruin this futuristically-plausible tale. No, you need to read They Both Die at the End for yourself.

Of course, you know what happens: the title doesn’t lie, but what occurs between call and end is phenomenal storytelling. Author Adam Silvera takes a bleak idea and spins it into a tale of friendship and caution-throwing and, because other characters are like spokes of a Mateo-and-Rufus wheel, we also see how small actions resonate in other lives through casual connections that are almost as meaningful as the purposeful ones. For sure, that’s heartbreaking, but it’s also darkly funny and oddly uplifting.

There’s also a certain “what if…” that lingers for a long time after you’ve closed the covers, which makes They Both Die at the End is a thought-provoker for anyone ages 14-to-adult. Start it, and you’ll be hooked all the way to the end.

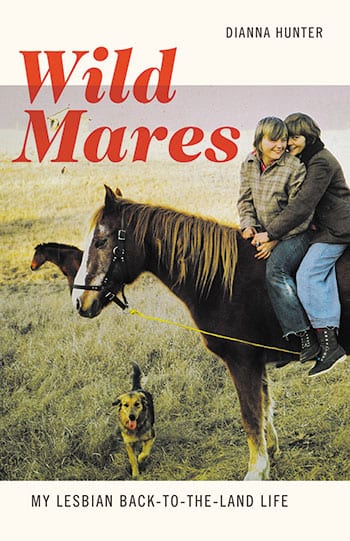

Wild Mares: My Lesbian Back-to-The-Land Life by Dianna Hunter (University of Minnesota Press 2018) $18.95; 241 pp.

Wild Mares: My Lesbian Back-to-The-Land Life by Dianna Hunter (University of Minnesota Press 2018) $18.95; 241 pp.

Growing up in rural South Dakota, Dianna Hunter learned what “queer” was long before she understood her own sexuality. She was “seventeen, cosseted, closeted, and clueless” then but, once enrolled in college and living in Minneapolis in an atmosphere of early-1970s feminism and LGBT activism, she “surprised” herself by coming out.

By then, classmates had introduced her to new friends, who introduced her to a lesbian community that raised her consciousness. Hunter learned how to be an activist, and she helped to create safe places for lesbians to socialize; when friends began to think about establishing a collective farm in Minnesota, she was highly intrigued.

“We were headed toward our dream and our vexation,” she says. “Women’s Land, Open to All Women.”

And it felt like the right “path to freedom.” At the first farm Hunter lived on, women and children shared the work and the bounty; “Voluntary poverty and group living” taught them that they didn’t need much money to get by, and they didn’t need men to care for livestock or outbuildings. Hunter soaked up every bit of information she could, and when it was time to move on, she and her next housemate rode their own horses more than 200 miles to another farm.

Through the years, there were other farms and other horses. Friends and lovers came and went, societal attitudes changed and, though now retired, Hunter was eventually able to buy and manage a dairy farm near Lake Superior.

“To many onlookers,” she says, “our lesbian-feminist back-to-the-land dream must have seemed strange and unrealistic, but we were far from the only ones who dreamed it.”

“Utopia” is a word that Hunter uses when recalling the first 15 years after coming out as a lesbian. No word could be more apt because, despite tales of lack and hardship, Wild Mares makes that life sound positively serene.

And yet there’s angst here, starting with a constant stream of people who move in and out of Hunter’s narrative, taking their drama with them and re-inserting it. After awhile, that seems like just more of the same and character fatigue may begin to set in; it doesn’t help that there are several farms involved, adding to the consternation.

Even so, Hunter’s introspection, her eagerness to do anything to find her “utopia,” and her love of the land take over and make this book palatable. Overall and in the end, it turns out to become a worthwhile look at non-traditional twentieth-century farming, and at Midwestern lesbian history. Yes, Wild Mares is a little relentless in its overly-peopled telling, but it’s also something different, for a change.

— Terri Schlichenmeyer