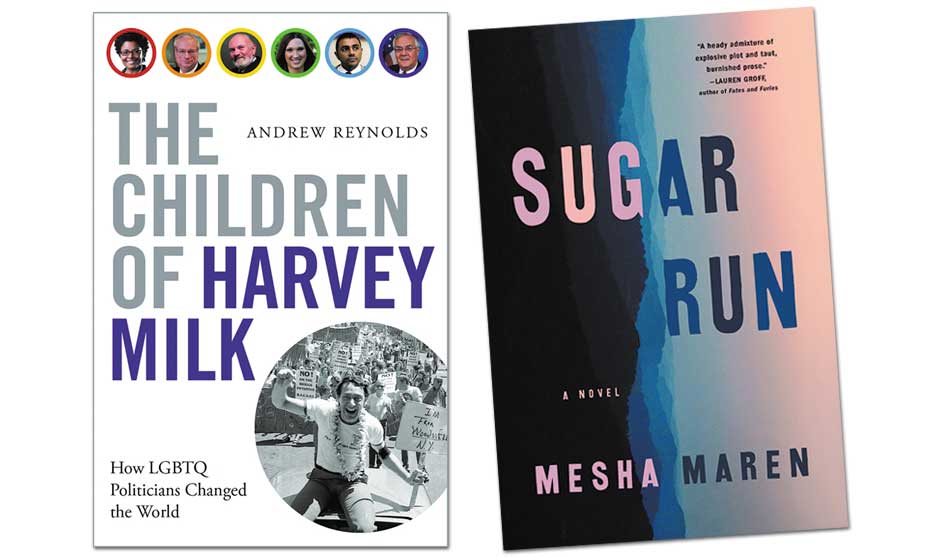

2 books to quench your reading needs

Sugar Run by Mesha Maren

(Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill 2019) $26.95; 320 pp.

She’d been told she’d spend decades behind bars. But there she was, ready to leave after only 18 years inside Jaxton Prison, a ticket in her hand and $400 borrowed from her brothers. Jodi McCarty was going home to West Virginia.

But first, she had to find Ricky. He was in Georgia, and she had time.

Ricky was the brother of Paula — Jodi’s lover and the woman she killed. It had always been Paula’s dream to get him far away from their abusive father. Jodi knew that was something she had to do now, so she headed to Chaunceloraine before re-starting her life on her grandmother’s farm. And in her search for Ricky, Jodi found Miranda.

When Miranda left her husband, she really only wanted attention but she got a surprise instead: He took their three boys and left her with no money. With no home, she was staying at the run-down motel near where Jodi had landed. Half-drunk one night, she ended up in Jodi’s room — and stayed.

Days before her first meeting with a parole officer in West Virginia, Jodi gathered Miranda and the boys she’d helped steal back, and she headed home, having talked Ricky into leaving with her. Jodi loved Miranda, and the cabin where she’d grown up was a good place to raise kids. It was in rough shape, but it was home.

As it turned out, it was someone else’s home: the land was sold for back taxes while Jodi was in prison, and fracking miners were buying up the area. Jodi didn’t know what to do and, as the pressure to care for her makeshift little family grew, she realized that she didn’t know Ricky or Miranda very well, either.

With the slam of a door, Sugar Run starts out with a stunned shiver and it sprints. Author Mesha Maren perfectly captures the surrealness of being snatched from an unwanted reality and hurled into one that doesn’t make sense. Even if you’ve only just driven past a prison, you’ll know the crush of it.

Back and forth the story goes, as we learn what happened when Jodi was 17. That’s a mandatory part of the tale, and it’s also, sadly, the cause of some disorientation since things begin to unravel as it’s populated with more and more people. Readers are rewarded with a gauzy, delicate ending but the last dozen pages make it tough getting there.

And that’s too bad, since there’s more overall-positive things to say about this book than not. Try Sugar Run, linger, and you might love it, but beware: you might also just as soon wish you’d left it.

The Children of Harvey Milk: How LGBTQ Politicians Changed the World by Andrew Reynolds

(Oxford University Press 2019) $34.95; 354 pp.

In the latter part of June 1978, Harvey Milk, known to locals as the Mayor of Castro Street, called former Army nurse Gilbert Baker and asked him to make something special for the upcoming Gay Freedom parade. At that time, the rainbow flag was a rebel flag, but Baker subsumed it into a symbol of Pride.

By the end of that year, Milk was dead and rainbow flags were still “rare and exotic” … as were openly-gay politicians. Just a handful of “LGB” people were in office around the world at that time; it would be years before the first openly-trans individual would be elected.

Andrew Reynolds tells their stories, beginning with a battle in New Zealand’s Parliament that was narrowly won, followed four years later by a marriage equality victory in nearby Australia. He writes of two gay politicians who squared off in Great Britain, noting that laws against buggery were still on the books when they ran. He tells of a Dutch politician who, by mere months, preceded Harvey Milk as the world’s first openly-gay man to serve in office. And he shares a story of politics in Ireland, “the first country in the world to pass gay marriage by popular referendum.”

Closer to home, Reynolds writes about Barney Frank, his first political battle for civil rights, and the “undercelebrated” woman who inspired him. Reynolds recalls the beginning of the AIDS crisis, and what it was like to be active in politics then. He writes of trans politicians Sarah McBride and Danica Roem, and the fierce but highly ironic story of Pauli Murray, whose great-aunt’s land donation helped build a university that ultimately denied bathroom access to trans individuals.

If you see The Children of Harvey Milk on a shelf somewhere, you may be confused by the title. Reynolds is referring to Milk’s spiritual descendants in political office who happen to be gay.

Fully half of Reynolds’ book is about politics overseas, and some of it won’t make sense unless you’ve got basic knowledge of how other governments work. Without it, you may not fully appreciate the significance of what you’ll read, though Reynolds is a good teacher. Here, readers will easily learn, and what they learn is absolutely inspiring.

For political animals, this book is an easy choice. For the slightly clueless, it’s a know-your-history book that doesn’t dwell strictly domestically. For a casual reader, it may be challenging but in the end, The Children of Harvey Milk could be the most informative book you’ll lay eyes on. █

— Terri Schlichenmeyer