A spate of gay memoirs shed light on conversion therapy, pro wrestling and two different trans journeys

Boy Erased: A Memoir by Garrard Conley (Riverhead Books 2016); $27; 340 pp.

Boy Erased: A Memoir by Garrard Conley (Riverhead Books 2016); $27; 340 pp.

From the time he was in fifth grade, Garrard Conley understood that he was a sinner. It became apparent with the thrill he got looking at men’s underwear, and the fantasies he had about other boys. Those things made his stomach flip-flop, and chilled his soul: “the increasingly blurry God” he’d known all his life would surely send him straight to Hell for being a homosexual.

At least that’s what his parents believed. Being gay was one of the worst things imaginable in Conley’s Baptist church; his father had received a call to serve the Lord, making homosexuality an even worse “stain” on their family.

Conley tried to will his sexuality away by having a girlfriend, a God-fearing “girl of his dreams” who came from the same Ozarks church community. Somewhat repulsed by her, he tried to ignore his gayness, begging God to take it away.

“Pleasehelpmetobepure.”

But it didn’t work. At college, Conley met a boy who outed him, shamed him and left him. Told by his father to accept a “cure” or leave his home, family, and education, 19-year-old Conley finally agreed to check himself into Love in Action (LIA), a Memphis “nondenominational fundamentalist… organization” affiliated with Focus on the Family, a “treatment” facility that would “fix” his sexuality.

“I could never count the number of times I’d sinned against God,” Conley said, but LIA made him do it; he was asked to investigate family sins, and remember things he needed to forget. He knew he was facing years of constant prayer and shame without his journal, literature or worldly ideas he’d begun to embrace in college; he was suicidal, angry, and he was still gay — but suddenly, with an unlikely source of support.

Boy Erased is one of those books that’ll make you think. And think, and think. There are so many nuances, so many things about this book to dislike: Conley says that he recreated from memory much of what happened because of confidentiality rules at LIA. Then again, he admits that there’s a lot he can’t remember, or has blocked out. Even his mother refuses to talk about what happened, but what they do remember is painfully near-incomprehensible.

And yet, Conley shows so much emotion in this memoir that it’s impossible to look away — and that includes a vibrant cord of anger that coexists beside a dawning realization that changes the course of this book. Absolutely changes it.

While it starts slow and the pace remains un even, this is a story that will niggle at your brain for days and days. Ultimately, love it or not, Boy Erased is a memoir that leaves an indelible mark.

In the Darkroom by Susan Faludi (Metropolitan Books 2016) $32; 432 pp.

In the Darkroom by Susan Faludi (Metropolitan Books 2016) $32; 432 pp.

On and off through most of her 40-some years, Susan Faludi had been estranged from her father. Even when he was in the picture, she was wary of him, a “household despot,” with a hair-trigger temper and a penchant for violence. She knew him, but she really barely knew him so, when she heard from her father for the first time “in years,” it was a surprise.

So was the message: Her father had become a woman.

He was born in Hungary in 1927, a pampered son of well-to-do Jews who sent him away as a child for reasons Faludi could only surmise. He’d come of age during the Nazi occupation and, according to stories, had survived through wits and bravery and had saved several lives. Because of her father’s reticence and tendency to embellish, though, Faludi never knew if those stories were true.

In September 2004, she boarded a plane to Hungary to meet her father, to learn who she really was, and to fill in the blanks about her.

It was a prickly endeavor: Never one to be forthcoming about her history, Faludi’s father dismissed most questions, refusing to discuss them, and she was reluctant to show Faludi any Budapest locales with familial significance. Father and daughter argued, Faludi gently prodded, her father pushed back, and she eventually gave Faludi names and places, important (sometimes falsified) documents, but scant insight.

For many reasons, Faludi learned, her father was a damaged soul. She’d been abandoned, misunderstood, terrorized … or had she been? Was Faludi’s father a victim of all she’d endured, or was she “an extremely effective liar?”

On the surface, In the Darkroom is a bit of a struggle to read. It’s quite wordy, filled with place names that may not mean much to readers who’ve never been to Hungary. I gave up trying to make sense of locales, but there’s no ignoring Faludi’s recreation of her father’s Hungarian accent. It’s everywhere in the text here, and not-so-charming after a few dozen pages.

And yet, what Faludi finds, what her father admits, feels like a noir whodunit with a different kind of victim. There’s intrigue here, derring-do, a deep mystery that still seems unsolved, and a protagonist who’s ultimately worthy of surprising sympathy.

That — the psychological heart of this book — arrives like a strobe in a photography studio, flash-flash-flash with the overall picture remaining tantalizingly fuzzy. In the end, I found that irresistible tease was worth overlooking the irritations, so go ahead. Start In the Darkroom, and see what develops.

Accepted: How the First Gay Superstar Changed WWE by Pat Patterson with Bertrand Hebert; foreword by Vincent K. McMahon (ECW Press 2016) $26; 258 pp.

Accepted: How the First Gay Superstar Changed WWE by Pat Patterson with Bertrand Hebert; foreword by Vincent K. McMahon (ECW Press 2016) $26; 258 pp.

Pierre Clermont understood poverty. As one of 11 children (plus parents!) in a two-bedroom apartment in a poor Montreal neighborhood, he was acquainted with wanting: of privacy, of hot water, even of food. He and his younger brother slept in a closet because there was nowhere else to put them.

Perhaps because he was one of a crowd at home, young Pierre longed to set himself apart and he loved to “create a show and get a crowd to come out and watch.” He thought of becom- ing a priest or joining the circus, so when his mother found a ticket to a wrestling match as a premium with a loaf of bread, Pierre became determined to see that show.

He was right — it was a life-changer. Pierre fell in love with wrestling and, because he knew someone whose father was a promoter, he began training to be a pro wrestler. He changed his name to Pat Patterson and, at around that time, he also began to understand why “girls just weren’t doing it for me.” He was gay, an ultimate admission that got him kicked out of the family home.

In Boston — his next home of many — Patterson had to learn English while he worked his way up the pro-wrestling ladder. He became the “bad guy” on the mat, and developed a ring persona. Also in Boston, he was set up with a man who “looked spectacular,” and with whom Patterson fell in love; he brought Louie Dondero into his act and his life for the next many decades, and they traveled the world on behalf of Patterson’s career. And though their relationship and their sexuality might have seemed out-of-place in an über-macho industry like pro-wrestling, says Patterson, “being gay turned out not to be an issue at all.”

Or was it? Did it have anything to do with the “scandal” to which he mysteriously alludes? Plenty is said about old friends, old matches, and off-work high-jinks but Accepted only merely bumps into that subject about which fans still argue.

But what’s in here for non-fans? Not much. Patterson’s love of pranks is clear in this book, which makes it mildly entertaining, and there are many times when he points out how times have changed. That’s interesting but, for non-fans, those bits are overwhelmed by names, travels, venues, organizations and more names that might not make much sense.

Yes, you’ll find a story of an openly-gay athlete at a closeted time in history in this book, but there’s a lot to sort through to get there. Non-fans might want to think twice about reading it, but for pro-wrestling followers, Accepted is a unanimous decision.

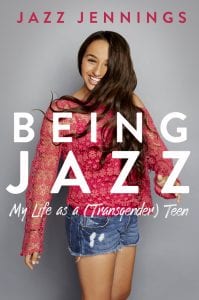

Being Jazz by Jazz Jennings (Crown Books 2016) $18; 272 pp.

Being Jazz by Jazz Jennings (Crown Books 2016) $18; 272 pp.

Since she was small child, Jazz Jennings knew that something was wrong with the way adults were acting toward her. Her parents dressed her in boy clothes, gave her trucks, and said things like “Good boy!” But Jennings knew even before she could speak that they were wrong. She was a girl, though her body said otherwise.

For most of her toddlerhood, Jennings (known then as Jaron) fought against anything that was remotely masculine. At age 2, she asked her mother when the Good Fairy was coming to change her into a girl; Jennings’ mother then realized that this probably wasn’t “a phase.”

At home, the Jenningses were fine with Jaron’s girliness, but preschool was different. Even then, there were bathroom issues; the principal of the school made concessions about school uniforms but Jaron wasn’t allowed to use the girls’ restroom. Shortly after that, she started calling herself Jazz, and Jazz often wet herself at school.

As she grew up, Jazz became an inspiration for many with gender dysphoria. She and her father fought for her right to play soccer with other girls — a battle that took years. She was upfront with friends — and even Barbara Walters on a TV interview — about being a girl in a boy’s body. She had plenty of haters, but she learned who her friends really were. She still struggles with depression at times, as well as typical teen issues but overall, she’s confident. And if she can help other transgender kids, then that’s all good, too.

Who’d ever thought that bathrooms would be such a hot-button issue in 2016? Jennings — who also appears with her family on the TLC reality series I Am Jazz — has been dealing with potty parity nearly all her life, which is just one of the topics she tackles in this memoir.

Right from the outset, it’s obvious that this is an exceptionally upbeat book. There’s almost no poor-me-ing here; even when she writes about struggles and occasional anger, Jennings’ cheery optimism is front-and-center. She gives props to her family, praising their easy acceptance and unconditional support, and acknowledging that many trans teens don’t enjoy the same familial benefits.

That praise can almost be expected, but I noticed one refreshingly unexpected thing: because of her honesty and openness, Jennings has become a role model, a status of which she seems nonchalantly abashed but secretly delighted, with a tone of pride there, too. Who could fail to be charmed by such straightforward authenticity?

While this book is supposedly for teens 12-and-up, I think a transitioning twenty-something could certainly benefit from what’s inside this book — as well as those who just need an education about the realities of being transgender. For sure, its buoyancy and optimism makes Being Jazz all kinds of special.

— Terri Schlichenmeyer