As with many queer Dallasites, I moved to the big city to shake off the dust of the small East Texas town I grew up in — in my case, Grand Saline. And as with many LGBT native Texans, my relationship with my hometown is complicated.

There are many aspects of my upbringing for which I’m grateful. Grand Saline was a safe, quiet place where I had a community of people who looked out for me. I credit my desire for a life of simplicity with an emphasis on family, love and relationships to my roots in Grand Saline.

On the other hand, Grand Saline has a race problem, the source of which depends on whom you ask. It has had a reputation of holding its prejudices for generations. If you ask most people in the community, you’ll likely be told this is false; if you ask people of color living in surrounding towns, you’ll likely be told this is true.

In 2014, Charles Moore — an activist Methodist pastor with a congregation in Grand Saline — self-immolated in a parking lot in the center of town, locally referred to as “the beargrounds.” Moore chose to end his life in an act of protest against the racism and bigotry that had been a longtime issue there. Inspired and disturbed by these events, one of Grand Saline’s own, James Chase Sanchez, partnered with Joel Fendelman to ensure Moore’s story did not die with him.

Man on Fire documents the life, activism, and eventual self-immolation of Rev. Charles Moore against a backdrop of an often well-meaning community, potentially in a state of denial. Sanchez and Fendelman will attend a free screening of the film, set for March 1 at 7 p.m. on the campus of Texas Christian University in Fort Worth. Before that, I visited with director Fendelman and producer Sanchez to discuss race relations, Rev. Moore’s support for the LGBT community and how they ended up making the film.

— Emily McGaughy

Dallas Voice: Can you describe your experiences growing up in Grand Saline, specifically those that led you to studying race and eventually creating Man on Fire? JCS: I started going to school in Grand Saline in seventh grade and there were all these racialized experiences that I didn’t know were wrong. I remember being called “wetback” and “beaner.” I remember one of the football team’s slogans was, “We’re all right because we’re all white.” These things didn’t bother me at the time because I was raised in a very white environment. But as I started going through college and grad school, I became really interested in why Grand Saline had all this racial discourse that was unique to it. I think my experiences of witnessing this racism and then moving away and seeing how that was wrong and how that’s different from the rest of the world made me interested. I started writing about it and, when Charles Moore self-immolated on June 23, 2014, I knew instantly that if I had one story to tell in my life. It had to be this story because it united all these interests that I had. I think my experience in my hometown really laid the foundation for this project.

Was Rev. Moore’s self-immolation a major catalyst to your study of race? My understanding is that you were studying this topic prior. Was Moore what inspired your work surrounding race? JCS: I was already studying some of the history of the town, but I didn’t really have a project that was pressing. I didn’t really have an exigence or an opportunity to make this work relevant. I was interested in this for a couple of years leading up to this, but then when Charles Moore self-immolated, all these pieces came together in a way that formed my dissertation and eventual book project. Something could’ve been written without Moore’s unfortunate death, but there’s no way it could’ve been what it has since become.

Joel, you’re from Miami but were living in Austin at the time. What led you to your involvement? What made you realize this was a story that needed to be told and that you wanted to be involved in telling it? JF: I’d never heard of Grand Saline until my involvement in this project. I was at the University of Texas getting my master’s in my third year and I was preparing to do a thesis project. Chase and I had a mutual friend, Kristen Lacefield, who was the girlfriend of my neighbor. She told me about Chase and about this project he was researching and using for a dissertation about his hometown. She sent me this article that Texas Monthly had published about Charles Moore and it just really struck me. It hit me in a deep place, knowing this person sacrificed in such an extreme way for his cause. It hit me so deeply. I, at that time, and even in this moment have lots of questions about what I’m doing to better this world. How am I giving of myself? That just really hit me when I heard what he did. I wanted to learn more; I wanted to learn about this town. I wanted to know if this affected this town, and if so, how?

He was committed to his cause so much that he gave his own life for it. By that measurement, any of us who cares about social justice and thinks intentionally about how we can make the world better, our impact is so small by comparison. I think all positive change matters, but as someone who cares about these things and wants to effect change, it’s a reminder of the vast difference between myself and individuals like Charles Moore.

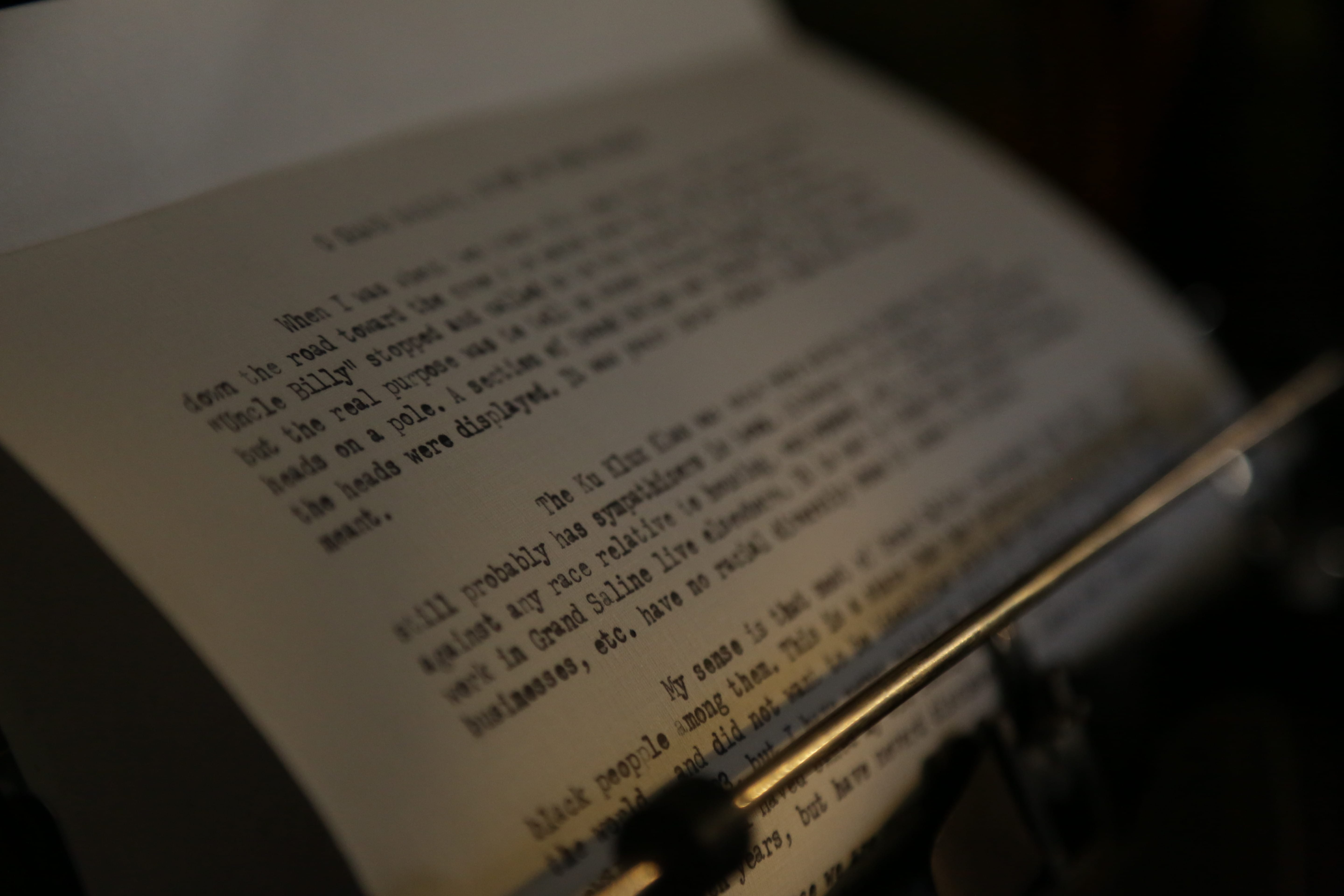

The narrative of bigotry in the South is nothing new. What was it about this particular story that felt important and unique enough to share with the world? JCS: You’re right, the story of bigotry is really the story of America and the South in particular. But I think what really fascinated me was that I remember the day that this happened. I’ll use this term because you’ll know what it is. I saw on Facebook people asking if someone had set themselves on fire at the “beargrounds.” I was already studying self-immolation and I was fascinated by it. The original story or rumor being spread was that Charles Moore was a part of the KKK and was asking for forgiveness. I was stunned by that. One of the witnesses put that on Facebook and was then threatened by Moore’s family because it wasn’t true. But that was the original story and I was fascinated by that. And then I read the actual letter. He tells a story about hearing about someone who was just lynched in Grand Saline and whose head was cut off and put on a pole. This was a story that he’d heard in the 1940s. Fast forward to the ’90s and 2000s when I was growing up in Grand Saline. I remember hearing these same stories. It was crazy to me that over 60 years, six decades, these stories about lynchings in Grand Saline were still being told. I was fascinated with why we were still telling these stories and knowing that someone was giving up their life for a cause in a very sacrificial way. As Joel said, it makes you think about what you’re doing in your own life. I’d never heard a story of someone sacrificing themselves for the greater good of other people, especially a white man doing it for people of color. I think there’s something special there. That was something that I wanted to investigate, so I was happy when Kristen Lacefield got me in touch with Joel and that he reached out to work on this project.

As someone who didn’t grow up in Grand Saline, I’d like to know your impression of Grand Saline. JF: Everyone we interviewed, met, connected with was very friendly and very congenial. There were hesitations from people we wanted to interview. Sometimes it took Chase reaching out a number of times. But generally people were pretty friendly. When we tried to talk about race, of course there were people who didn’t want to talk about that so much. I’d never been to a place like Grand Saline prior. It felt like back in the 1950s — Main Street, the old town vibe — at least what my idea of the 1950s was. The way people talked about things was like the 1950s, too, as we talked about the self-immolation of Charles Moore, the way people spoke about black people and race. Anywhere more urban or progressive — no one says the term “the Negroes.” It wasn’t intentional to be offensive; everyone was good-hearted. Anytime you put a camera on someone for an hour, it’s like a microscope. I’m sure if you did that to me, things might not come out the best that they could.

JCS: I think Joel’s right that it’s just the culture that surrounds the town. It keeps it stagnant in the sense of talking about race, especially. The discourse is the same that it was a long time ago. Saying things like, “Black people need their own community and if they don’t have their community they feel lonely” — having these excuses on why black people don’t live in this town. The culture hasn’t had this sort of interaction with people of color, black people especially. That’s something that showed up in a lot of the interviews.

Based on what you know about Charles Moore, how much of is advocacy and activism included serving as an ally to the LGBT community? JCS: He advocated quite a bit for the LGBTQ+ community in a few different ways that don’t always show up in the film. I guess I’ll first say that the film is looking at Charles Moore’s death, but it’s also a biography of Grand Saline in some capacity. We really focus on Moore’s impact on Grand Saline and his racial views. Some does focus on his other advocacy but not too much in the film because it could’ve sprawled into a two or three-hour documentary. But he went on a multiple week fast in the early to mid-1990s to protest the Methodist church on their stance on having gay and lesbian bishops in the church. He was in Austin at the time. This was when there was a national Methodist meeting there. He got the church to agree not to exclude people from the church because of their sexuality. Also, he was pondering self-immolation for a few years. He almost self-immolated on the Southern Methodist University campus in protest of how gay and lesbian people were treated on campus. He drove to SMU and wrote a letter that’s part of his archives, talking about almost doing it, but he just couldn’t move himself to do it. I think that LGBTQ rights were very important to Moore’s ministry and advocacy. He really almost gave up his life in protest of SMU’s handling of these issues.

JF: He was also involved in one of the first churches in Austin that welcomed gay people. That was very controversial for the Methodist Church. A lot of people that we interview in this film were congregants of that church.

JCS: He also allowed PFLAG to hold their meetings in his church. I think that’s why a lot of gay and lesbian people joined his church — because of how open he was in the early ’90s in comparison to other Christian churches.

Within the progressive movement, there’s a lot of debate on how best to bridge the gap between us and conservative, rural America. After spending all this time studying the life of Charles Moore and the Grand Saline community, what are your thoughts on how we can best accomplish this? JCS: There are some obvious parallels when it comes to identity politics and rural America. I think this 1950s discourse on racism and racism parallels with how people in these communities talk about gay and lesbian people. I truly believe that the best tactic to change the discourse is to have open dialogues and open conversation about these issues. You hear these stories of people saying they were bigots until they became friends with a person of color. Or they were against homosexuality until their daughter came out as a lesbian. And their stances change when they know real people who fit into these identities that they don’t always come face to face with. I think that having confrontations and dialogues and conversations with people from these different identities and showing that they’re human is one of the best things we can do. That’s always good in theory, but it’s sometimes hard to do.

JF: And a change in leadership. If the church could, as leaders in these communities, change their stance on these things, that would make a difference. A lot of people feel they can’t go against the church. If we could have some leadership open up and start this dialogue and acknowledge that maybe they’re wrong, that would be a huge step.

If someone they look up to as much as they probably do their pastor or leader of their church acknowledge that they’re questioning their own principles, it would make it acceptable for everyone to be honest about that. JCS: I think Joel’s absolutely right. It comes down to the leaders, whoever they may be, taking that leap of faith, making themselves vulnerable and showing that you can go against your constituents and believe something outside of the norm. That’s really important and should be seen more often than it is.

Do you think positive change is happening in the hearts and minds of people in Grand Saline? And, if so, do you think this project could’ve inspired it? JCS: I would say absolutely. The most common interview question we get is, “What change did Charles Moore create?” Of course it’s hard to see less than four years removed from what happened. But, I know people whose hearts and minds are absolutely changed because of Moore’s death. It hurt them and it impacted them and it changed the way they thought about race and racism. It wasn’t this big revolution like Moore wanted, but there were people effected. I hope that our film in some capacity becomes a way to open up a dialogue about race and racism in Grand Saline. It’s not just labeling everyone as a racist and a bigot, but how this perception needs to be talked about. There were somewhere between five and ten people who reached out to me and thanked me for working on this. There was a young woman who had a child with a black father. Her dad kicked her out of the house because she had a child that was half black. She reached out to me and thanked me for this project. She expressed the need for this to be talked about and that there were people in town getting away with bigotry. It’s normalized and it’s accepted. I don’t want to say this represents everyone, but there are people who’ve been effected by bigotry and are vulnerable. We hope that this film changes the discourse around this.

You gave those people a voice — like the young girl. Maybe she didn’t have the opportunity to tell this story in such a big way, so you told it for her. JCS: Not everyone has the means to create a documentary about their hometown. We hope that we can help those marginalized voices.

JF: Charles Moore self-immolated in a parking lot, kind of in the middle of nowhere. There wasn’t a lot of press that came from it. Most people we’ve shown the film had not heard of this. We do ask that question. Does this change anybody in the town, beyond the town? It’s an ongoing thing. A lot of people, in the moment, would say it didn’t really make a big impact, but it’s a process. It’s all these small grains of sand. I think the film, in some ways, is a living an organism and an extension of what Charles did. We’re going to show the film on the 28th in Tyler. There will be a lot of people, we hope, from Grand Saline showing up there. We’re showing it at TCU and hopefully a number of other places in Texas and beyond. Change happens in small steps. That’s what we’re trying to do.

It really came at the perfect time because you were filming before the election. And now since the election, these conversations about small towns like Grand Saline are happening all over the place because those of us who are progressives are wondering how this happened. Where did we go wrong? We have to face the fact that there are communities all over the country who feel disconnected from us and our ideals. We have no choice but to do what you did and step into these communities and have these conversations. I think progressives want to know how we can do that better because we obviously haven’t done a great job.

JCS: There were so many times that I felt uncomfortable because these were friends, family of friends, people I knew. When I put a camera in front of them and interviewed them about race and Moore, it was so uncomfortable.

Those are things we didn’t talk about growing up there. JCS: It’s so uncomfortable in the moment. It was also so rewarding. Making yourself vulnerable can be tough, but ultimately I think it’s valuable in order to have progress.

JF: I’m so thankful they allowed us to put them in this film. Their vulnerability, their honesty is a vehicle for us to talk about this.

And you have to honor that. Regardless of whether you agree or disagree, you have to honor that they put themselves out there, which is not easy for anyone to do. JCS: Absolutely.

JF: I’m not any better than anyone we interviewed. I’ve got my own stuff, my own bigotry, my own bias. It’s a process. One of the pastors we interviewed said, “We’re all recovering racists.” We were interviewing our brothers and sisters, in the human sense. We’re just trying to help each other along to get to a better place where we can all live in an equal society.